Is a picture really worth a thousand words?

To Korean-Detroit artist and designer Mike Han it is.

Han has created Disparate, an online art exhibit about race, diversity, discrimination and segregation in America, which can be viewed at the Siren Hotel virtually until May 8 with a closing reception via IG Live @mikehan_detroit at 8 p.m.

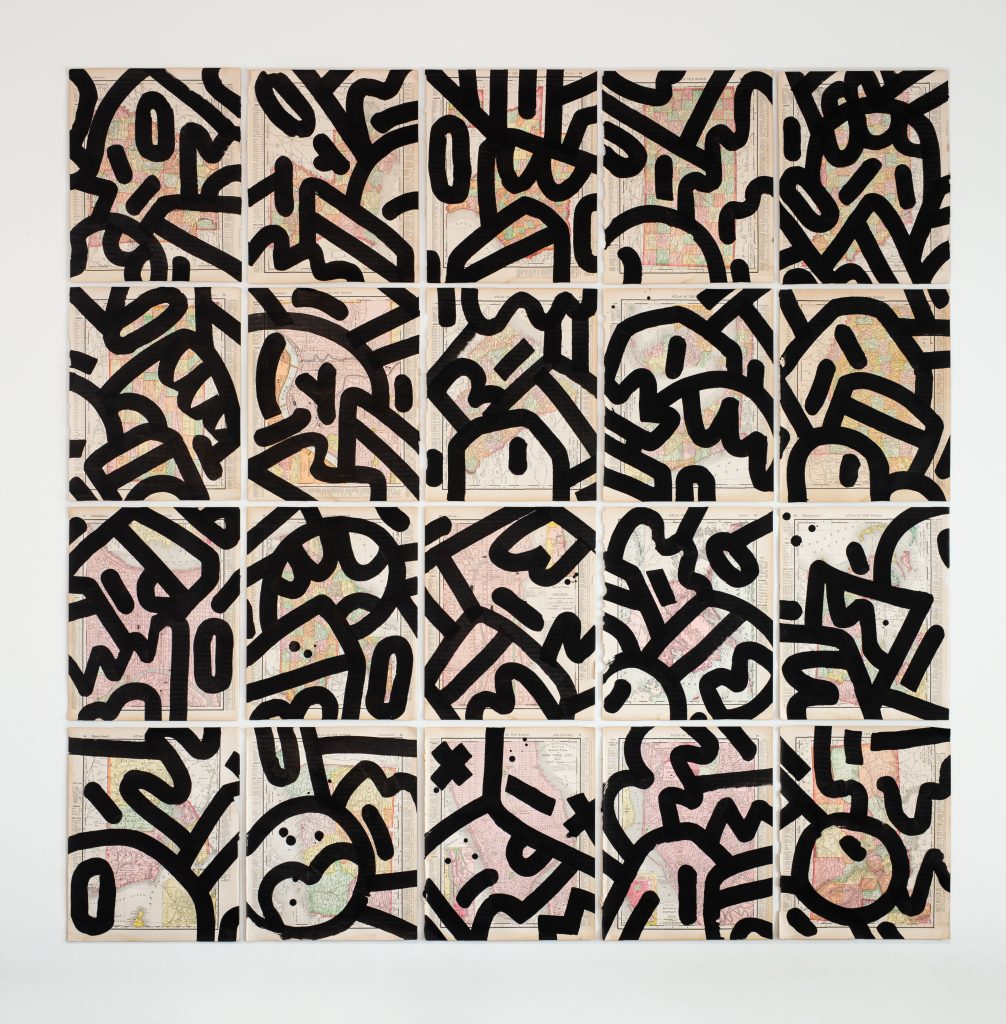

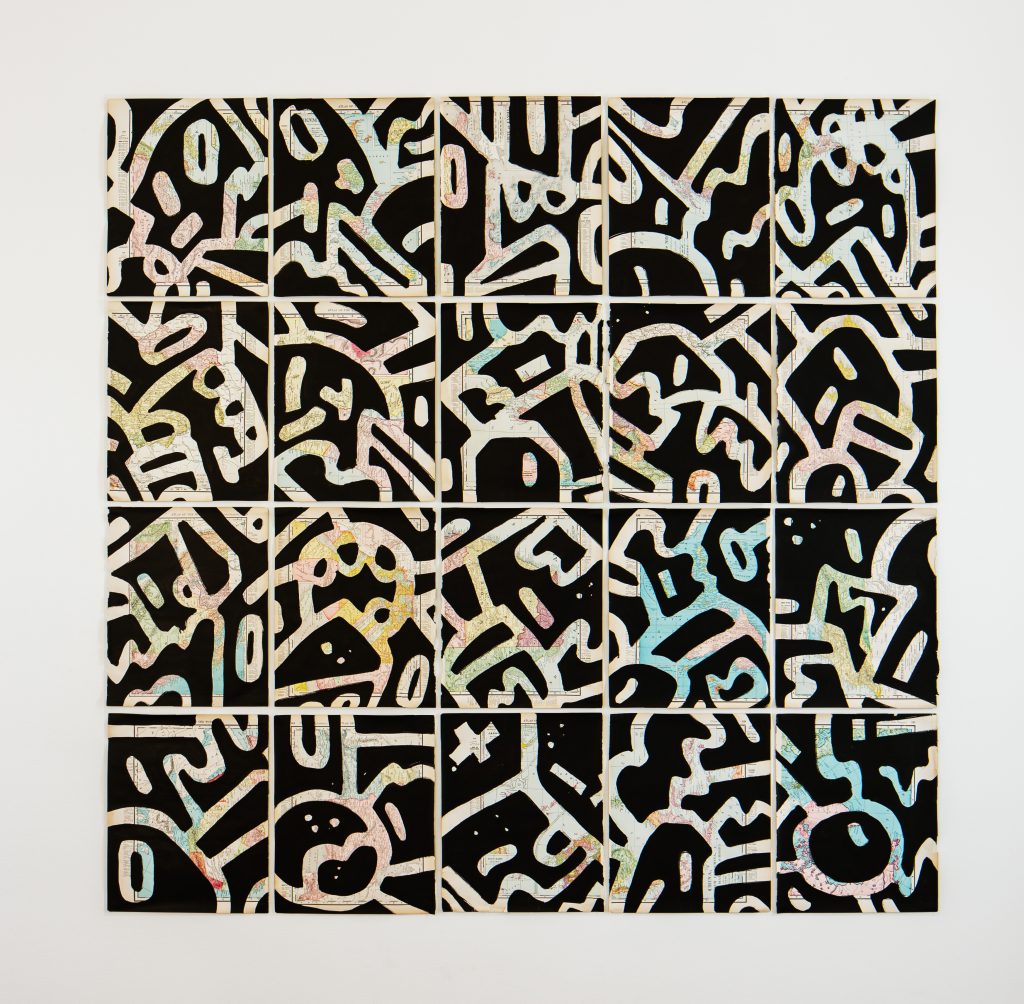

The paintings are on torn vintage atlas pages of states across America and countries from around the world and include negative space and Asian-inspired calligraphy created with graffiti tools.

Disparate is the right name for the show. Things that are disparate are made up of fundamentally different and often incongruous elements, much like the patchwork quilt of people we have in the U.S.

Through these pieces Han hopes to start a conversation about Asian Americans experience with prejudice, race and diversity. He means a conversation, not a lecture.

These are issues that as an Asian American Han knows quite a bit about.

“Asians are often viewed in America as foreigners, and sometimes treated as though they don’t belong,” Han says. “This is true for immigrants, naturalized citizens, and natural born citizens of Asian descent. Disparate hopes to cultivate a better understanding of what being American looks like.”

The pieces are complementary works hung on opposite sides of the room – those made from U.S. atlases on one side and those made from international ones on the opposite side. The two pieces also have their color schemes inversed to show a similarity across the globe.

“It represents the connectiveness,” says Han, who worked on the pieces during an artist’s residency at the Siren. “It shows the two parts of the world are connected.”

The art “reveals our stark differences and attempts to illustrate how connected we are … our unique individuality, the chaos of life, and the seldom seen truth that we are all connected,” he says.

For every purchase, 60 percent of the proceeds will go to Hate Is A Virus, an organization that combats hate against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

Han is very familiar with those biases. He believes he has suffered some self-esteem issues from spending a significant part of his life as an “other.”

Asian Americans often feel like they are perceived as more foreign than their white or black counterparts, he says. It’s been an issue even though he was born in Michigan.

” From some people’s vantage point, I am not an American,” says Han.

He is a Cheongju Han, a Korean royal clan known as House of Han, whose history dates back over 1,000 years. Han is the first born in America on his mother’s side who immigrated to Detroit’s Cass Corridor in the early 1970s with her family.

Despite being born in Michigan, Han spent much of his childhood in Connecticut where he went to a Korean church and went to Korean classes. His best friend, who happened to be Caucasian, would often ask his mother to make the traditional Korean food Han’s mother would prepare.

Then Han moved to West Michigan for the tail end of elementary school, middle school, and the beginning of high school. There things got a more complicated, and he began to feel more alien.

“It didn’t matter to be Korean on the East Coast,” says Han. “In West Michigan in was not okay.”

Kids asked odd questions, like if he knew Kung Fu or “what kind of Chinese” he was, or they didn’t believe he was born in the same state as they were

While the hurt was there as a young child today Han says today he know they were not necessarily being hateful or insulting, but instead curious.

“When they ask me these things it isn’t because they hated me,” he says, but he still remembers the bullying he endured in high school there..

Han moved to Plymouth for the tail end of high school, where he was asked to join an Asian American group at the school. He then told them it was dumb to have such a group and was called “racist.” It was a word he never thought would be associated with him.

To me, racism is malicious,” he says.

Han has since dived head-first into his Korean heritage, even attempted to be a chef, who combines Korean and Japanese foods.

He has visited South Korea and was saddened to find out he was once again the outsider. There he was viewed an American who had trouble using the currency.

It hammered home one big truth – he was a Korean American, a product of two cultures, but to some degree outside both.

“I experienced that I was not actually in their culture either,” says Han.

Now, he lives in Detroit, but still faced some of the same bias.

For example, sometimes he is still asked where he is from, followed by “no, where are you REALLY from?”

For example, sometimes he is still asked where he is from, followed by “no, where are you REALLY from?”

There are bright spots.

A Korean American friend of his whose child was enrolled in a school in Detroit asked what was planned for Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month after Black History Month ended. The school had not considered or planned on a curriculum. The child’s mother was offered, and accepted, the opportunity to prepare a lesson. It was a chance educate the children about the Asian American heritage.

Han would like to see more of that kind acceptance. That’s why he wants his art to start a conversation instead of a lecture. He believes it is important to teach people about his culture and experience, instead of block them out.

Han believes that too often people are blocked out for saying something ignorant or insensitive, when explaining things may be a better solution. A solution he admits is perhaps an unfair burden on the person who may feel insulted, but a more valuable option in the end.

Hate crimes against the Asian community are up, and Han thinks what the activists are doing to combat that is great, but that it can be overreaching sometimes.

“(When) we are yelling at each other nothing will get done,” he says, advocating instead for a more street-level view based on understanding and education.

This may just be the beginning of this journey for Han.

He and some Korean American friends have a plan to reach out to the suburbs and build a coalition to help others not only understand, but experience, his culture.

Editor’s note: All photos by Diana Paulson