Detroit’s campaign to bring the nearly 40,000 rental properties into compliance with the city housing code by 2020 defies logic. These codes were intended to prevent neighborhood deterioration. This blitz, however, will accelerate abandonment and decimate both low-income and middle-class communities.

Rental property owners will have six months to register their units, bring them up to code, have them inspected and obtain a certificate of compliance and occupancy from the city. Tenants in units not brought up to code will be able to escrow their rent payments. If the landlord does not pass muster within 90 days, the escrowed rent will be returned to the occupant. Non-paying residents cannot be evicted for withholding rent during the non-compliant period. And landlords who are delinquent in paying property taxes will not be issued certificates of compliance.

Preventing more neighborhood decomposition would be a reasonable proactive goal if Detroit had enforced these policies when the city was thriving. It didn’t.

In the 1950s, for example, Detroit had the largest percentage of homeowner/occupied properties in the United States. Most were single-family units. Since then, the city’s population – and correspondingly homeownership – has fallen dramatically. Today, less than half of Detroit residents are homeowners. That number is dropping precipitously, most notably among the age group with the greatest ability and inclination to purchase a home.

In the 1950s, for example, Detroit had the largest percentage of homeowner/occupied properties in the United States. Most were single-family units. Since then, the city’s population – and correspondingly homeownership – has fallen dramatically. Today, less than half of Detroit residents are homeowners. That number is dropping precipitously, most notably among the age group with the greatest ability and inclination to purchase a home.

People who remain in the city overwhelmingly suffer from high unemployment and poverty rates that render them ineligible for mortgage loans. Their options are to rent, or in some cases, become squatters.

Since the 1970s, many rental units were allowed to slide with impunity into deep disrepair. Homes in depressed areas are typically too deteriorated for code enforcement to have anything but a negative effect.

Faced with low home values and low rents, landlords may not have the resources to navigate a costly, complex and inefficient city bureaucracy to bring a house into conformance with a stifling city code. Thus, imposing measures that are beyond the economic ability of property owners to achieve, or pass along to renters, sets up a domino effect that only benefits demolition crews.

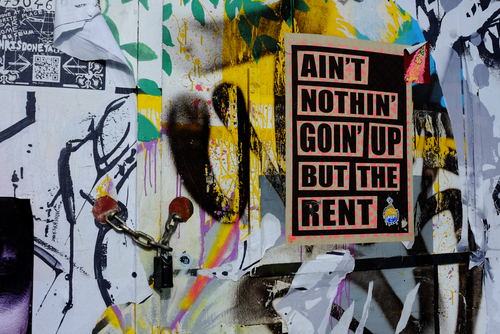

The city already loses thousands of homes to the wrecking ball every year, a pace that far outdistances new home construction. Thousands more are on the demolition list as a result of high property taxes, foreclosures and high homeowner insurance rates. Reversing this trend cannot happened without a scorched earth mentality. If the intent, however, is to force the poor out of the city, planners couldn’t have come up with a more insidious, albeit effective strategy.

Some landlords will ignore rental registration rather than subject themselves to exorbitant repair costs. Those who cannot sell, repair or rent their properties may decide the best option is to cut their losses by torching them to collect on the insurance. This leads to further abandonment, a lowering of the demand and supply of low-income housing and further shrinking of the tax base.

Attempting to impose code enforcement on a city still in free fall will bring Detroit to its knees. Will the initiative’s legacy be a lesson on how extreme regulation personifies unintended consequences?

Lead image by HipKat/Shutterstock